Sutherland Grove

Conservation Area Appraisal No.47

Contents

Part One: Introduction

Outline of Purpose

The principal aims of Conservation Area Appraisals are to:

- Describe the historic and architectural character and appearance of the area which will assist applicants in making successful planning applications and decision makers in assessing planning applications;

- Raise public interest and awareness of the special character of their area;

- Identify the positive features which should be conserved, as well as negative features which indicate scope for future enhancements.

It is important to note that no Appraisal can be completely comprehensive, and the omission of a particular building, feature, or open space, should not be taken to imply that it is of no interest.

This document has been produced using the guidance set out by Historic England in the 2019 publication Understanding Place: Conservation Area Designation, Appraisal and Management, Historic England Advice Note 1 (Second Edition).

This document will be a material consideration when assessing planning applications and as an evidence base for the Local Plan.

What Is a Conservation Area?

The statutory definition of a conservation area is an ‘area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’. The power to designate conservation areas is given to local authorities through the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservations Areas) Act, 1990 (Sections 69 to 78).

Once designated, proposals within a conservation area become subject to the national policies outlined in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), the adopted London Plan policies, and the conservation policies set out in the Council’s Local Plan.). Our overarching duty, set out in the Act, is to preserve and/or enhance the historic or architectural character or appearance of the conservation area.

Public Consultation

Public consultation on the draft Appraisal was carried out between the 10th February and 24th March 2023.

This document was approved by the Planning and Transportation Overview and Scrutiny Committee on 4th July 2023 and the Executive on 19th July 2023.

Designation and Adoption Dates

Sutherland Grove Conservation was designated on 23 November 1992.

This Appraisal was adopted on the 31st of August 2023.

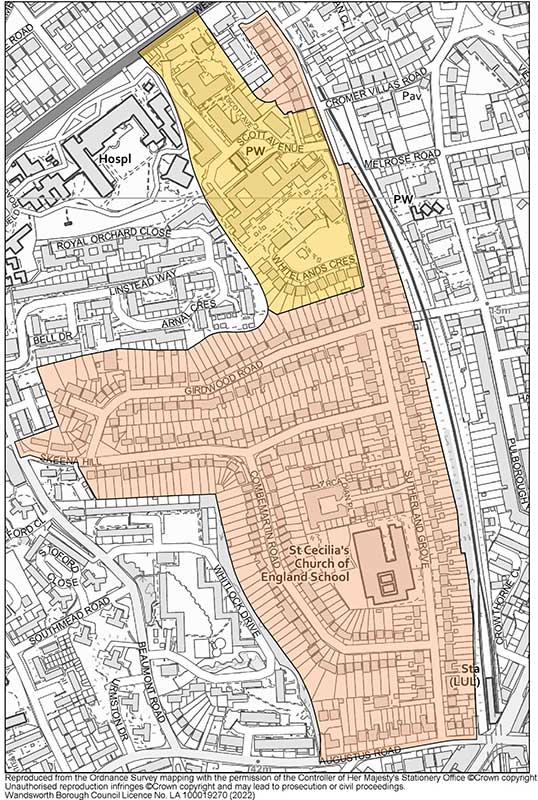

Map of Conservation Area

Summary of Special Interest

The special character of this Conservation Area is derived from the homely domestic 1920’s–30s suburban housing with generous front gardens in a dramatic hilly streetscape coupled with the sophisticated urbane architecture of the former Whitelands College.

Historic Development

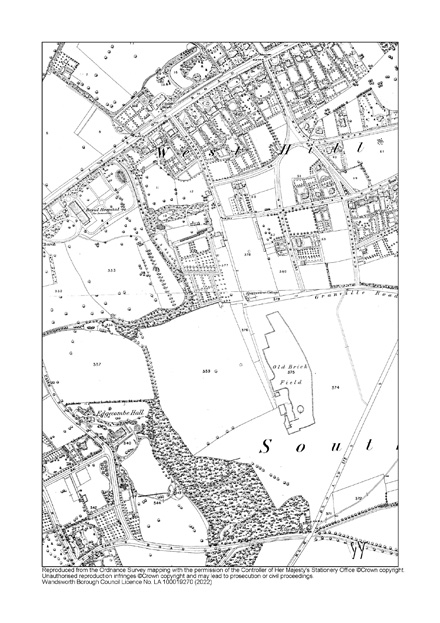

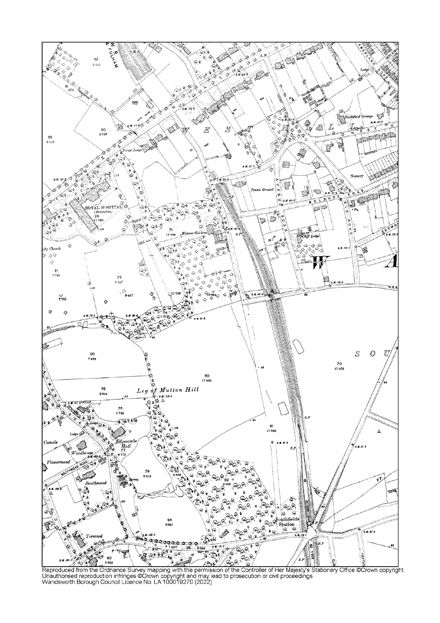

With a small number of exceptions, the area which comprises the Conservation Area was mainly open fields, known historically as ‘Leg of Mutton Hill’, possibly in reference to the shape of the wooded area, the line of which loosely followed the route of Combemartin Road. The land was part of the grounds of Edgecombe Hall, a large villa fronting Beaumont Road, and there was a footpath crossing the area around the edge of a coppice, along the line of the present-day road. The OS Map 1869-74 & 1896 (Figs. 1&2) shows the largely vacant land, save for a house to the north-east labelled ‘Melrose Gardens’ and Forest Lodge to the north, fronting West Hill. Also on the 1896 Map is Southfields Station, which opened in 1889. The station was opened by the District Railway on the 3rd June as part of an extension from Putney Bridge station to Wimbledon. The extension was built by the London and South Western Railway (L&SWR) which, starting on 1st July 1889, ran its own trains over the line from a connection at East Putney to its Clapham Junction to Barnes line. The section of the District line from Putney Bridge to Wimbledon was the last part of the line to be converted from steam operation to electric, with electric trains running from 27 August 1905.

Main line services through Southfields were ended by the Southern Railway (successor to the L&SWR) on 4th May 1941, although the line remained in British Rail ownership until 1st April 1994 when it was transferred to London Underground. Until the transfer, the station was branded as a British Rail station.

Fig.1: OS Map 1869-7

Fig. 2: OS Map 1896

Fig. 3: Southfields Station c1900. Source: Wandsworth Heritage Service

The arrival of the station, as is typical, spurred development in the surrounding area, and the OS Map 1916 shows that in the next 25 years, to the east, the terraces of Southfields had been laid out, while to the west, the high ground was occupied by large Victorian villas with extensive gardens (later replaced by the large post-war council estates centred on Beaumont Road). Sutherland Grove has also been laid out by this time, and there are two semi-detached dwellings at its southern end illustrating the beginning of the development of the wider housing estate.

Fig. 4 - Sutherland Grove c1915

The bulk of the estate was built over a period of 10-to-15-year period in the 1920s and '30s, as evident on the 1930s OS Map which shows a largely complete estate, with the exceptions of the west side of Skeena Hill, the east side of Girdwood Road, and the larger detached homes to the north of Sutherland Grove. At the same time, the Borough Council opened Wandsworth School on Sutherland Grove, at the heart of the estate, to provide secondary education for the rapidly increasing local population. To the north of the area, a large swath of land was attained by Whitelands College for their newly constructed campus.

Fig. 5 - The Royal Hospital, 1923, illustrating the beginning of construction to Sutherland Grove, visible at upper right

Whitelands College (Gilbert Scott Building)

A woman’s teaching college founded by the Church of England’s National Society in 1841, the original college was located at Whitelands House in Chelsea. Across the early years of the 20th century the college flourished and came to be regarded as one of the foremost women’s teacher training colleges in the country. At the end of the First World War, it was decided that the school needed a new home, removed from the grime and noise of the King’s Road and more conducive to study. Winifred Mercier, then the Principal, set about identifying a new site and eventually chose the current location off West Hill. Determined that nothing but the best would do for future teachers, she persuaded the College Council to employ Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, architect of Liverpool Anglican Cathedral, Battersea Power Station, and other prestigious public buildings, to design the new college.

Fig. 6: The Opening of the College by Queen Mary, June 1931

The building was constructed to a design by Gilbert Scott, in collaboration with Ms. Mercier, from 1928-1930. The impressive building was officially opened by Queen Mary in June 1931. The building is Grade II listed, as is the adjoining chapel constructed at the same time.

The building was vacated by the college in 2005 and converted to residential use and the grounds subsequently redeveloped, by a mixture of detached homes, terraces, and new flat buildings.

The estate was largely complete by the 1940s, as illustrated on the OS Map 1947-1952. The 1960s saw expansion of the school facilities, with Wandsworth School extending far beyond its original 1920s quadrangle, and new flat blocks constructed to the north of Whitelands College (OS Map 1951-1978).

Fig. 7: Whitelands College and environs, 1937, illustrating the largely complete neighbourhood. Note gap at upper left, later infilled

A new school was consented in 2000 to replace the Wandsworth School in the grounds to the south, and Saint Cecilia’s Cof E School was constructed over the following years. The demolition of the 1960s school building allowed for the redevelopment of the 1920s school and its grounds, with permission granted in 2002.

Circa 2004, Whitelands College and its associated buildings were put forward for conversion / demolition given the impending vacancy of the school from the building. The redevelopment involved the conversion of the main building and chapel to private residential use, as well as the demolition of the adjacent Gloucester Court, West Court, Student Union building, Faunthorpe House, and smaller ancillary buildings. These were replaced with a mixture of building types, primarily detached and terraced buildings to the south and east, and larger, more typical block flats to the north.

Part Two: Conservation Area Appraisal

Location and Setting

Sutherland Grove Conservation Area is comprised of Sutherland Grove, Girdwood Road, Skeena Hill, and Coombemartin Road, as well as newer development, which took place within the grounds of the former Wandsworth County Secondary School and Whitelands College.

The Conservation Area is located between West Hill and Augustus Road, with the closest local centre of Southfields immediately to the south-east, where there is the District Line Underground station, the tracks of which form the eastern boundary of the Conservation Area.

Topography

The slope of the land, particularly the rise from Sutherland Grove towards the west and the high ridge of Beaumont Road, is a key part of the character of the area. The east-west roads curve up the slope of the hills rather than cutting across them, a feature of the area which adds significantly to its charm. The change in topography grants for a variety of garden types given the placement of houses within the plots, with some sitting above steeply sloped or stepped gardens, and others sunk below the level of the road with gardens and drives rising in front.

Buildings and Townscape Overview

The predominant building type within the Conservation Area is large detached and semi-detached residential properties with generous and mature front gardens. This provides the principal characteristic of the townscape, one of a pleasant arcadian inter-war suburb.

Fig. 8: Typical housing typologies to the Sutherland Grove Character Area

With some small exceptions, the residential buildings were built over a ten-to-fifteen-year period in the 1920s and '30s. An earlier exception includes the small group of late Victorian houses at the southeast end of Sutherland Grove (Nos .2-14) which have the more solid appearance of buildings of that period and are much altered. The group at the northwest end of Sutherland Grove are also earlier and different from the prevailing type. They are larger detached dwellings in an Arts & Crafts style, each individual but exhibiting common elements of detail and materials - e.g., tiled roofs, timber porches, and multi-paned windows.

The rest of the residential estate has much more cohesion despite a great deal of variety. Though constructed by different building firms, the houses are all of the late Edwardian suburban style popular at that time, incorporating a range of architectural motifs from the Arts & Crafts, 'Tudor-bethan' and Queen Anne Revival styles. This creates a visually rich appearance, but also an overall character which hangs together well.

The Gilbert Scott Building, formerly set in a generous and mature landscape, formed an important part of the suburban setting – its redevelopment into a second residential area has somewhat altered this original character, and created a smaller yet discernible character area. The development surrounding the building is a mixture of detached homes, terraces, low-rise flats, and more typical blocks of flats which reach up to five storeys. Although much of the landscape surrounding the Gilbert Scott Building has been retained and repurposed - development to the north is taller and denser, giving the impression of a more urban setting.

Spatial Analysis

The two-character areas are experienced separately given their density, building typologies, and the typography of the area, but share a residential character, with an openness and verdant appearance common across both. Gaps between buildings and set back from roads, with mature planting surrounds, form important aspects of both areas and create a strong suburban experience. The shifting topography allows for changing views and breaks up development, even when more closely spaced together, from appearing as one consistent building line or mass.

Character Areas

The Conservation Area can be divided into two-character areas which are predominantly defined by their building typologies:

- Area 1: Sutherland Grove Area - comprising Sutherland Grove, Combemartin Road, Girdwood Road, and Skeena Hill, with large, detached and semi-detached interwar housing;

- Area 2: Whitelands – this area is more urban in character with denser/taller contemporary development, which surrounds the listed namesake building and its surviving gardens. Comprised of Whitelands Crescent, Whitefield Close, and Scott Avenue.

Character Area 1: Sutherland Grove Area

Summary Description

The South Area forms the majority of the Conservation Area and includes most of the historic buildings, largely constructed beginning in the 1920s to the late 1930s, with pockets of Victorian and 1940s development. The area is characterised by its large detached or semi-detached dwellings set in large, often well planted gardens, in a range of materials and styles, yet coherent as a diverse group. The topography of the area plays a key role in how it is experienced, impacting placement and positioning of the dwellings, and revealing different views as one transitions through the area, ascending or descending the hills.

Townscape

Sutherland Grove

Fig. 9: A small group of larger detached dwellings with Arts & Crafts detailing characterise the north end of Sutherland Grove

Sutherland Grove is a long gently curving road with perhaps the most varied townscape. The north-western side of Sutherland Grove consists of a group of large detached large 2-3 storey Arts and Craft style individually designed residences set back from the road with individual drives / parking spaces off the street (Fig. 9). These extend southward to the junction with Cromer Villas Road, where the District Line tracks ascend to the surface to the east, and the boundary wall of the former college begins. Here, the street is dominated by the east boundary of the former college grounds, formed by a robust 2m high solid brick wall fronting the pavement, which extends until Girdwood Road (Fig. 10). Only the entrance gate relieves this barrier, to give views into the extensive mature grounds and strong mass of the main building, as well as the modern flats of the Whitelands character area (Fig. 11).

Fig. 10: The robust boundary wall of the former college dominates the west side of Sutherland Grove for much of it's length

Fig. 10: Entrance gates relieve the boundary and mature planting to the Whitelands area softens its appearance

The eastern side of Sutherland Grove picks up again south of the junction with the railway and presents 2 storey white rendered and brick panelled semi-detached properties of the late Edwardian suburb style, again individually accessed off the main road into private drives or drives with garages.

Fig. 11: Typical detached pairs to the south section of Sutherland Grove

Fig. 12: Despite some variation, there is a consistency in the streetscape

Fig. 13: This house retains many of its original features including the door, porch, and casement windows. The roughcast finish and tiles are also characteristic of the Area, though many others have been painted or rendered.

A short gap to the west, Arcadian Place leads to the converted Wandsworth School and surrounding residential development, which despite its larger than average scale at 3 storeys, is set within a rather well concealed enclave. The east group are set behind pastiche buildings constructed as part of the development to flank the entrance, keeping interruption to the Sutherland Grove streetscape is minimal, though the houses themselves are larger and of an uncommon design to the prevailing character of the street (Fig. 14). This allows for a clear and inviting view through to the principal façade of the school, the most attractive feature of the area. The north group of flats are also of 2 storeys but with a larger footprint, but well set back given the large rear gardens of Sutherland Grove and Skeena Hill.

Fig. 14: Pastiche houses flank the entrance to the Wandsworth School development to rear

Fig. 15: Large semi-detached buildings within the school enclave

Fig. 16: The former Wandsworth School converted to residential use

Fig. 17: Terrace type building toward the rear of the enclave

The domestic street pattern is interrupted, again on its west side, by the buildings and grounds of Saint Cecilia’s School. The large H-plan building is 3 storeys, and the substantial grounds are primarily hardstanding, and though the building clearly communicates its function, is a visual disruption to the otherwise consistent appearance of the area. The long boundary wall is also a physical and visual barrier, and its style and scale are neither coherent with that of the building nor the streetscape more generally.

Fig. 18: Saint Cecilia's School

At the extreme southern end, it again reverts to the classic suburban street pattern, and on the east side is the earlier Victorian group at Nos. 2-12, a mix of detached and semi-detached groups identifiable by their uncommon pitched roofs, but overall the group has been heavily modified (Figs. 19&20).

Fig. 19: Part of an earlier Victorian group to the south end of Sutherland Grove

Fig. 20: Part of an earlier Victorian group to the south end of Sutherland Grove, some of which have been heavily modified, adjacent to later development

Augustus Road

Fig. 21: Augustus Road typially has deeper gardens and taller boundary walls

Augustus Road is most similar in appearance to Sutherland Grove, with common semi-detached typologies continuing to the west until No. 43, a much larger and earlier 20th century house which marks the boundary of the Conservation Area. A gradual incline of the road adds interest to the stepped roofscape, which remains legible despite some interruptions by various interventions. Front gardens are larger and almost all have been lost to hardstanding which diminishes the suburban character common to the rest of the Area. Taller boundary walls and more frequent traffic intensify this impression.

Backland development is more common to Augustus Road, but the set back from the road allowed by such deep gardens means only glimpsed views toward development is possible, while planting and sympathetic materials mitigate their appearance, making a neutral contribution to the Area.

Girdwood Road

Fig. 22: Girdwood Road

Girdwood Road consists of semi-detached and terraced 2 storey properties with attics, consisting of brick and rendered panels with exposed gable timberwork, hipped roofs, and canopied entrance porches. Some properties have vehicle access onto drives and garages, but many have been converted or full hardstanding introduced. The road rises steeply upwards to the west end to meet Skeena Hill. The west has a more varied townscape, with more building typologies found, including 1.5 storey backland development at Nos. 72/72A, a number of detached dwellings, and a cul-de-sac with a group of mirrored pairs.

Fig. 23: Girdwood Road is characterised by a number of building styles and materials which add richness to it's character

Fig, 24: mock-Tudor style dwelling

Fig. 25: Another typology, with green tile roofs, a feature found only to Girdwood Road

Fig. 26: A consistent group of pairs at the cul-de-sac

At the junction of Girdwood Road and Skeena Hill are a small group of slightly later (1940s) semi-detached houses including Nos. 67 & 69 Girdwood Road and Nos. 60-66 (even) Skeena Hill (Fig. 27). Although their scale and form are slightly different from the surrounding dwellings, they offer a transition in appearance from the larger villa type houses to the east to the slightly smaller detached dwellings more common to the west side of the Conservation Area.

Fig. 27: 1940's infill development

Overall, the character of Girdwood Road is Arcadian Inter-war suburban vernacular set in a partially tree lined and grass verge streetscape.

Fig. 28: To the west the road rises to meet Skeena Hill

Skeena Hill

Fig. 29: The west section of Skeena Hill is characterised by large detached dwellings placed close together

Skeena Hill has a mixture of both detached and semi-detached dwellings more balanced than the surrounding roads, and though the housing typologies are varied, there are often groups of similar styles houses adjacent to within very close vicinity to each other. It also has the only examples of the typology with large double storey front gables (Fig. 31), which adds further richness to its diversity.

Fig. 30: Semi-detached pairs are characteristic of the north and east sides, and there is rich variation to their designs

Fig. 31: This housing typology is only found on Skeena Hill

There is also more variation in the placement of the dwellings within their respective plots, informed by both the gradient topography of the street and its central curve at the junction with Combemartin Road. Many houses are stepped or set at a slight angle to address these elements, which often exposes side elevations more so than elsewhere in the conservation area. Houses to the north are typically sunk into their gardens while those to the south sit higher in theirs, giving the impression of a taller building line despite identical building heights. Despite these steep slopes, drives remain common, and many gardens have been lost to full hardstanding, creating unattractive gaps and detracting from the suburban character. While there is a relatively good standard of surviving finishes in comparison to the other roads, there are also several examples of painted houses in odd colours, which stand out awkwardly.

Fig. 32: The steep slope of the road is apparent in this view, with houses to the left (north) sunk in their gardens while houses to the right (south) are raised

Fig. 33: The curvature of the road affects the placement of the houses, with their side elevations prominently exposed

Fig. 34: 1940s infill development similar to that at Girdwood Road - the rendered and painted wall is overbearing to the streetscape

Combemartin Road

Fig. 35: Combemartin Road

Combemartin Road differs in that it is primarily large, detached dwellings with only a few examples of semi-detached houses. There are typically pairs or small groups of houses of the same typology, though much alteration has sometimes eroded the group to a degree where the relationship is difficult to read. Given the close-knit building line and similarity in typologies, there is a relatively consistent scale and roofscape, at two storeys plus hipped roofs, though again, intervention has worn at this character and introduced obvious inconsistencies.

Fig. 36: Combemartin Road is characterised by larger detached homes, often in pairs or groups

Fig. 37: A variety of housing types, with richly planted gardens

Combemartin Road is defined by its varied topography, primarily sloping down to Sutherland Grove, and by its large, closely spaced detached villa type dwellings, set in large, well planted gardens. Unlike Skeena Hill, the placement of the buildings within their plots does not respond to the curvature of the road, but rather, remains consistent along its length. While this constant building line would typically result in an overbearing terracing effect, the incline of the road means that each house sits at a slightly different level than its neighbour, avoiding this allusion. The effect is, however, somewhat evident closer to Sutherland Grove, where the ground levels out. The hipped roof forms are also key to this, creating oblique views through gaps created by the spaced peaks of the roof form. Roof alterations along the street have been extensive, and many insertions into the roofscape infill these gaps and degrade this stepping feature, blocking views through or adding excess massing to elevations.

Fig. 38: Hipped roofs create important gaps which help break up the roofscape

Fig. 39: Detail of hipped roofs

Spatial Analysis

To the Sutherland Grove Area, wide pavements, generous gardens, and detached or semi-detached dwellings create a strong urban character, with views through the area, and through properties, enhancing this experience. The gentle curving of roads and sloping topography of the Area also allows for shifting views, changing the experience as one travels through, and further breaking up development. The undulating streets also mean side elevations and roofs often become more apparent in oblique views, making unsympathetic alterations more obvious.

While there is no public open space within the character area, the wider pavements, verges, and well cared for gardens are inviting and create the character of a garden neighbourhood.

While the redevelopment of the former Wandsworth School created an enclave at Arcadian Close with a slightly different character than the surrounding development, it retains a good degree of planting and the important spacing between buildings, breaking up the massing of the group and allowing for views to gardens and development beyond.

Fig. 40: Houses typically have little space between them to Combemartin Road, but terracing is avoided by views through to rear gardens and the use of hipped roofs

Fig. 41: Houses to Girdwood are more generously spaces and the slope of land behind allows for views to the gardens and rear elevations of houses to Skeena Hill

Fig. 42: The topography of the area breaks up the roofscape

Fig. 43: The closeness of the buildings means they are sensitive to change, and the infilling of gaps with larger dormers can create an undesirable terracing effect

Architecture

Several elements combine to reinforce the cohesiveness of the area. All the houses are two storeys with a similar relationship to the street frontage, varying only to reflect and reinforce the curves of the roads themselves. The scale and proportions are consistent, despite the great variation in the arrangement of elevations and features such as picture windows, recessed and extended porches, bays, and front gables. Houses are generally paired and semi-detached, in more of a ‘cottage’ or Arts & Crafts Style, with a few individual detached properties, mainly at street corners. It is interesting that there is no typical house, but there are some smaller legible groups, and none of the styles look out of place amongst its neighbours. Likewise, materials vary a good deal, with both yellow and red brick used, and many houses have fronts of pebbledash, smooth render, hanging tiles, and half-timbering. While this variety adds richness to the character, there has been in an increase in the introduction of plain white render to the detriment of this character. While render can certainly form part of this mixture, its extensive or exclusive use is out of character and erodes the intended assortment. Reinstatement of original finishes can help restore this feature and would be of benefit to the appearance of the conservation area more broadly.

Figs. 44-47: Some of the different architectural styles and materials found in the area which contribute to its variation and richness

Original windows, typically casement dependent on the period of the host dwelling, were timber, but there has been much replacement by aluminium and plastic units, which although often in patterns matching those of the originals, fail to replicate the quality and integrity of the originals. Doors have received a similar treatment, though there are still a good number of original doors which have survived, or high-quality replicas. The style of door unique to Sutherland Grove has a top third round window divided into six panes, while to the remaining streets, historic doors had a single oval pane.

Figs. 48-50: Historic window patterns, typically casements with smaller fanlight, often with leaded windows

Fig. 51: This type of door is found on Sutherland Grove and a good amount of originals survive

Fig. 52: A door with a more oval windows is found to the rest of the character area

A consistent feature is the use of plain clay tiles on the roofs, though again modern alternatives are widely evident. There are a few surviving examples of original green glazed pantile roofs, particularly to Girdwood Road, which are very attractive and add variety and visual interest to a group of similarly styled buildings, and which should be retained.

Fig. 53: Green roof tiles are characteristic of Goodwood Road. This house also has attractive original casement windows

Roof forms are almost exclusively hipped, apart from the late Victorian group to the south which have period appropriate pitched roofs. Hipped roofs form an important aspect of the Conservation Area, creating a harmonious and consistent roofscape, which can easily be spoiled through unsympathetic alterations. They are also a key feature in the spacing of the buildings, by creating a greater sense of space when buildings may be physically close together. Many roof alterations have occurred which have imposed on the original consistent character of the area, and are often unsympathetically executed, whether out of scale with the host dwelling or in inappropriate locations. The incline of the area and irregular building line of development also means any interventions will be dependent on the individual dwellings circumstance and positioning, with side and rear elevations more visible varying greatly with these factors.

Fig. 54: Hipped roofs are the most common roof type and a key characteristic of the roofscape

Fig. 55: A hip to gable conversion imbalances the pair

Fig. 56: Excessive / imbalanced interventions

Fig. 57: Side elevation become particularly apparent at curves and corners

Similarly, side extensions are increasingly common but uncharacteristic to the area, and can easily create a harmful terracing effect, infilling the important gaps between buildings and interrupting longer views between houses.

Fig. 58: Side extensions can also cause imbalance and compete with the host dwelling, while infilling important gaps

Porches are another common element adding variety and richness, and there are examples of both inset porches and simple projecting pediments. The infilling or extension of porches is increasingly common, which alters the appearance of front façades, especially as they are often carried out in unsympathetic and contrasting materials. Porch alterations and front extensions are not characteristic of the area.

Figs. 59 & 60: Original porches are pleasing and add simple, charming decoration to front elevations. Infilling is not characteristic and changes their character

Fig. 61 & 62: Recessed porches are also common

The former Wandsworth School's redevelopment created a small enclave of a different style than the surrounding development. By far the best building on the site, the original 1920s school, is built around a courtyard, though only its main pediment is visible from Sutherland Grove, and it is best appreciated by travelling into the group. The modern residential buildings are three storey red brick masonry in stretcher bond cavity construction with a hipped slate roof and ornate tile / brick detail to the window and door openings. There are white painted timber windows to the front, side, and back elevations in double glazed bespoke pattern. The six fronting the school have awkward projecting dormers.

Fig. 63: The materials and scale of the contemporary residential buildings are contextual to the historic school building

Boundaries, Drives, & Entrances

Boundaries within the area are inconsistent and much altered but follow a general scale and materiality. Historically, timber fences would have been regularly employed, but these are increasingly rare, with some modern replacements evident particularly to Combemartin Road. At present, timber is most commonly observed to rear and side boundaries, and their retention in these areas helps to preserve the suburban character of the area more broadly. Front boundary walls are most often replaced with brick in varying heights and designs, some with capping/piers etc, but all are relatively low. Metal is not a feature of the area, and where it has been introduced, it is obviously uncharacteristic. The finish of the brick matches the host dwelling. Low walls allow views into front gardens and these views, as well as the gardens themselves, helps preserve the openness and verdant character of the area. Some boundary walls have been rendered where the host dwelling has also altered its external finish, but this is uncommon and uncharacteristic.

Fig. 64: Simple timber fences would have traditionally been employed as boundary treatments

Fig. 65: Brick boundary treatments are typically low with planting behind

A number of walls in unsuitable materials have crept in and the loss of some to front garden parking has resulted in gaps. Of particular note are the raised front gardens of properties near the junction of Combemartin Road and Skeena Hill, with a series of stepped brick walls adjacent to steps.

Entrance gates to pathways and drives are infrequent, and most prevalent to Girdwood Road. Where they do exist, front gates are often simple swinging gates of a plain design in timber.

Gates to driveways have been introduced but create a sense of enclosure which is not apparent throughout most of the area. Where narrow drives exist, again, simple swinging gates of a basic design in timber or occasionally cast iron appear and fit with the varied boundary typologies. Some wider gates have been introduced by decreasing the width of the boundary wall, which changes the appearance of the entrance as a whole and is disruptive to the streetscape. Modern electric gates are often bulky and of unsympathetic materials, and appear overly urban, creating a visual and physical barrier.

Fig. 66: Metal gates and powered gates are uncharacteristic and visually obtrusive

On the south side of Sutherland Grove there is a long unattractive boundary wall to Saint Cecilia’s C of E School which is constructed of different colours / finishes of brick and has a very low wall with metal rails above. The entrances are flanked by robust brick piers with large metal gates. The scale, materials, and design of the boundary are all inappropriate, and uncharacteristic of the Area, and are not cohesive with the existing streetscape.

Fig. 67: The long gate to Saint Cecilia’s in uncharacteristic in its form and materials

The robust brick wall on the west side of Sutherland Grove demarcates the grounds of the former Whitelands College from the surrounding residential estate and forms a physical and visual barrier between the South and Gilbert Scott Character Areas.

Fig. 68: The robust brick wall to the former college grounds characterises most of Sutherland Grove

Open Space, Gardens, and Trees

Figs. 69 & 70: Heavily landscaped and mature gardens add a pleasing verdant and character, particularly to Combemartin Road

There is no significant public open space within the character area, but there is a strong verdant character given the abundance of generous, mature planted gardens, in combination with the hilly landscape which allows for views through multiple greenspaces concurrently. Front gardens are often well maintained with a variety of planting types, which offers a changing appearance with the seasons but maintains a sense of green year-round. A richness of planting types, including various heights and volumes, contributes to the sense of a communal garden character, which is most evident to Combemartin Road. Large trees are also evident in rear gardens from gaps between buildings. While hedges can form part of this variation, robust hedges used to block gardens can disrupt longer views through the area and create a sense of enclosure, contrasting with the character of the surrounding gardens.

The replacement of front gardens with hardstanding further erodes this character, often creating abrupt, visual gaps, and is highly uncharacteristic of the Area.

Figs. 71 & 72: Paving of front gardens disrupts the garden character and creates visual gaps

Street trees are common to the area, with smaller species the most common. Cherry and pear trees can be found in most of the area, which offer attractive spring blossoms and greenery throughout the warmer months. Sutherland Grove differs in that it is lined with more robust maple and plane trees, giving a stronger sense of an avenue. Additional street trees were planted to commemorate the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee in 2022.

Fig. 73: Street trees are common, and their presence has recently been bolstered by new plantings celebrating the Diamond Jubilee

Grass verges are found to Girdwood and Combemartin Roads, which are an attractive element that not only offer a visual separation between the road and pedestrian areas, but contribute to the green, suburban character of the streets. The verges are in various conditions, and many have been replanted with native plant species which has allowed for the growth of taller grasses and wildflowers, and these verges are often more attractive than those treated as an extension of lawns. In addition to contributing to the garden character of the conservation area, these wild verges are also lower maintenance and attractive to pollinators.

Fig. 74: Verges planted with wildflowers contribute to garden character, biodiversity, and are low maintenance and drought resistant

Fig. 75: More traditional verges still make a positive contribution to the streetscape and create visual separation between foot and vehicular traffic

Paving

*As part of a Highway Maintenance Programme, there are ongoing footway and carriageway maintenance works which will see the wholesale replacement of existing pavement within the CA – description below reflects condition as of July 2022, to be amended*

Paving in the character area is consistent, apart from Combemartin Road, and are a patchwork of bricks, pavers, and asphalt. Bricks are purple and red, most often in a herringbone pattern. Pavers appear throughout the area except for Girdwood, and are grouped in ‘islands’, which do not extend the full width of the pavement. The pavers are either consistent in a single colour or are a mix of light grey, dark grey, and red. Piecemeal repairs have often been carried out using asphalt as an inexpensive option, forming unattractive smooth and dark patches which visually stand out from the otherwise neutral palette. Kerbs are granite and of a good quality.

The pavements to Combemartin Road have been replaced (summer 2022) with light purple/grey bricks in a 90° herringbone pattern to drive entrances and light grey/sand pavers between, which is a cleaner finish that differs from appearance of the rest of the character area.

Fig. 76: Existing paving is a mix of pavers and bricks with granite kerbs

Fig: 77: Bricks follow a herringbone pattern

Fig. 78: The new paving is lighter in colour and rationalises the layout, with bricks to drives and pavers between them

Within the former Wandsworth School complex, the access road is stone setts with tan coloured pavers

Fig. 79: Stone setts within the former Wandsworth School complex

Fig. 80: Sand coloured pavers

Street Furniture

Street furniture is uncommon and primarily restricted to typical traffic/parking signage common throughout the borough. Grey modern lampposts are unremarkable. There are simple wooden bollards to Girdwood Road and Combemartin Roads.

Fig. 81: Timber bollards are common and add further separation to pedestrian areas from traffic

Character Area 2: Whitelands

Fig. 82: The Grade II Listed former Whitelands College, converted for residential use

Summary Description

The Gilbert Scott Building forms the focal point of the Character Area, sitting central to the surrounding development in a portion of what were formally much larger grounds. Although behind a high wall, which separates the former college grounds from the residential estate, the building still has a significant effect on the area because of its bulk and position towards the top of the hill.

There are two groups of buildings within the area: the main college building itself and its ancillary buildings, including the adjoining chapel, lodge, gate, and walls, as well as the historic Forest Lodge; and the surrounding modern accommodation.

Townscape

Gilbert Scott Building and Early Development

The main block and chapel (both listed grade II) are by Giles Gilbert Scott, constructed in 1928-30 in dark red/brown brick with some stone dressing and pantile roofs. The size of the main block, four and five tall storeys, and its mass, makes it a dominant feature of the grounds and the surrounding streets.

Fig. 83: The Gilbert Scott Building forms the focal point of the Character Area

Fig. 84: The Grade II Listed chapel has also been converted to residential use

The gates (listed grade II) are a relic from the original college site in Chelsea and are 18th century ornate wrought iron. The adjoining lodge (also grade II) is by Gilbert Scott and is of the same date and similar style and materials to the main buildings.

Forrest Lodge (grade II) is an Italianate Victorian villa (c.1865) in stock brick with stone dressings, and hipped slate roof; it is three storeys and basement. Beverley Gate is a four storey 1930's building, and both address West Hill, heightening the sense of privacy and separation of the Gilbert Scott Building, which was accessed and concealed behind their robust boundary walls. Their height also helps to screen some of the more contemporary development, which infilled the space between the main building and its satellites.

Fig. 85: The gates from the original Chelsea location were relocated to the West Hill entrance, and are also Grade II Listed

Fig. 86: Beverly House

Fig. 87: Forest Lodge, Grade II Listed

Redevelopment of Whitelands College

The mid-2000s saw the vacancy of the college and subsequent development of its grounds. The new mixed residential development involved new homes that attempt to reference the surrounding urban character, utilising existing aspects of layout, material choice, and typology to influence construction. Buildings were designed with a limited palette of local materials and architecture, and while this is most obvious to the ‘villas’ at the south of the area, the domestic vernacular is less obvious to the north, where blocks of flats replaced former student accommodation buildings.

The simple, modern design of the buildings is intended to engage an architectural aesthetic that is consciously subservient to the formal dominance of the main Italianate building. In the area, there are four main building typologies: villas, terraces, small apartments, and blocks of flats.

Villas

Fig. 88: The Villa style houses are large semi-detached dwellings

The villas line the south section of the character area along Whitelands Crescent and were designed to address the building typology found elsewhere in the conservation area, being semi-detached homes of white render and red/brown brickwork. Architectural references, such as hipped roofs and render, have been specifically taken from the surrounding context and the positioning of these buildings means they have rear gardens backing onto existing rear gardens of the adjoining semi-detached properties along Girdwood Road. The gentle curve of the crescent breaks up the street and has a more organic feel than the formal street plan which informs the rest of the redevelopment. The houses are taller than is typical for the Conservation Area, at three stories with hipped roofs, and are narrower and more closely spaced together. The hipped roof form helps maintain and enhance gaps between buildings and a sense of openness found elsewhere in the Conservation Area and allows for longer views through to the double backed gardens.

Small Apartments

Fig. 89: The small apartments are set in spacious gardens

The smaller low-rise apartment blocks are located between the villas and the Gilbert Scott building and are 3-5 stories in height, with inset top storeys and undercroft carparking below. This height and massing provide an architectural transition between the 3 to 5 storey height and dominance of the main building, which sits on slightly higher ground, and the 3 storey family Townhouses to the south. The blocks are more cuboid in form, which reduces their bulk and allows for more generous landscaping surrounding them, so as not being overbearing to the surrounding development or the setting of the listed buildings. The position of the buildings also emphasizes the axial relationship of the public corridor through the site and the more formal plan of the character area compared to the organic curves of the South Area.

Terraces

Figs. 90 & 91: Two typologies of short terrace are utilised

There are two groups of terraced townhouses which are located on the two cul-de-sacs of Scott Avenue. The terraces are three storeys with pitched roofs and share a palette of materials with the rest of the development. The east group has projecting elements to its ends, which are clad in timber. As with the smaller blocks of flats, the terraces are a transitionary scale from the lower development along and behind Sutherland Grove, and the larger Gilbert Scott building – however, the typology is unique to the area and when considered in the context of the surrounding detached properties, particularly in views to the south where the listed building is not visible, they appear slightly overbearing in their massing. The lack of gaps between houses is uncharacteristic of the area and restricts longer views into the Character Area.

While the terraces have relatively reasonably sized gardens, the eastern group is concealed by the robust brick wall to Sutherland Grove, while the western group blocks views to their gardens by being set forward within their plots with only parking and a small strip of green to the front. The terraces, therefore, contribute more to a dense, urban character, more so than the garden character of the villas and South Character Area.

Flat Blocks

Fig. 92: The larger block flats are restricted to the north side of the area

Fig. 93: The larger blocks create a more enclosed, dense, and urban character

Fig. 94: Some of the materials and colours are not particularly characteristic to the area

The larger blocks of flats follow a similar design pattern and palette to the smaller apartments, but range from 3-5 storeys and are much larger, comprised of rectangular buildings connected in different orientations. While materials are similar, timber cladding is more obvious. The upper storeys are set back to mitigate some of the bulk, and the linear placement helps emphasize the access road through the area. Hannay House is a later development and slightly different in its design and scale, at four storeys to transition to the scale of the historic buildings which front onto West Hill. It also incorporates another material, buff brick, which references the modern additions to the adjacent listed hospital building rather than development within the Conservation Area.

Parking Garage

The parking garage is constructed of sympathetic materials but has no architectural significance

Spatial Analysis

Fig. 95: An east-west walking path helps establish an axial arrangement

There is a planned axial arrangement to the Character Area, which is intended to guide, attract, and encourage pedestrians and cyclists to travel through the area. This is established through a grid-like pattern, which is centred on the Gilbert Scott building at centre. The formal landscaping helps heighten this arrangement, with consistent parallel walkways which result in rectangular gardens, often enhanced with robust and regular boundary plantings.

Fig. 96: View into the area with the Gilbert Scott building terminating

Fig. 97: North-South route leading to communal garden

The south side of the character area is more open, with the greatest portion of the former grounds surviving in the large, shared amenity space at Whitelands Crescent. The gentle curve of the road and wide spacing between the small apartments adds to the openness of the area, with the gentle slope rising to Gilbert Scott building heightening its prominence.

Fig. 98: The large communal garden at Whitelands Crescent contributes to the landscape character

This openness is retained to the side of the Chapel building, but otherwise the north side of the area has a more urban character, with taller buildings and increased density. Here, amenity space is limited, and gaps between buildings are primary limited to access roads, often terminating in other development, which creates a sense of enclosure.

Fig. 99: Dead ends create a sense of enclosure and density

At the extreme end, fronting onto West Hill, are the small collection of more historic buildings, which are set into more traditional plots of land, some of the front gardens of which have been converted into car parking. The arrangement of buildings here fits more with the streetscape of West Hill itself, where larger detached buildings are set back from the road behind tall boundaries, creating a sense of privacy and prominence.

Architecture

Fig. 100: The listed building follows a general Italianate style

The elements comprising the former Whitelands College, including the main building, chapel, gate, and walls, are all similar in their materials and form, utilizing red brick and concrete, with stone details and hipped pantile roofs. Timber sash windows dominate the elevations of the main buildings and are apparent on the ancillary buildings. The elements range from a single storey up to five and are robust in their scale. The buildings, from the large block plan of the former college to the small entrance lodge, are symmetrical in their design, and there is value in their appearance as a group.

Fig. 101: The same materials are utilised throughout the more contemporary development

The limited palette of materials and design typology unifies the newer elements within the Character Area and are somewhat responsive to the surrounding context. They represent a subservient scale and appearance to the central listed buildings, with neutral, cool colours contrasting with the rich reds and browns of local brickwork, as well as the surrounding greenery.

Materials which have been replicated include render, timber, and slate tiles, and while these materials are more characteristic of the Sutherland Grove character area, the group is still distinct in its contemporary design and form, that it is certainly distinguishable as its own character area. This is somewhat reflective of the failures of the intended design / layout, which aimed to create a more cohesive transition from the existing residential development rather than a separate group.

Fig. 102: Timber employed to give horizontal emphasize to lessen the impression of height

The use of rendered side walls is intended to minimise the apparent bulk while upper storey treatments in cedar and brick are employed to reduce the apparent height of the building, particularly to the Villas and Terraces. To the apartments and flats, the timber and brickwork panels are interspersed across elevations to provide vertical and horizontal emphasis.

Open Space, Gardens, and Trees

The only public open space within the Conservation Area can be found within this Character Area, remnants of the robust grounds, which surrounded the former Whitelands College. With the redevelopment of the building, land to the south in particular was preserved and heavily landscaped, to not only preserve the setting of the listed building but provide amenity space to the new residents. The communal spaces are quite formally planted, with regularly spaced trees and plants of similar size and type, although some mature trees were retained.

Fig. 103: The grounds surrounding the central complex have been retained as communal areas

Fig. 104: The large garden at Whitelands Crescent is the primary open space in the area

Residential gardens are predominately restricted to rear gardens to the detached homes and terraced groups, but small strips of front gardens, occasionally with ornamental trees planted, help maintain the appearance of a garden neighbourhood and break up the drives to avoid an overly urban appearance.

To the north of the area, the blocks of flats are more closely spaced together and surrounded by access roads, and there is a more of an urban sense of character. This is somewhat mitigated by attractive dense plantings of a rich variety of types and heights of plants in the immediate surrounds, which helps soften the appearance of the development, and help create a visual experience when travelling through the area.

Fig. 105: Attractive, mature, and varied landscaping helps soften the appearance of larger blocks and adds to the verdant character of the area

Paving

Pavements to the residential streets are multicoloured pale stone setts which are not a material that is found elsewhere in the Sutherland Grove Conservation Area, with granite kerbs. The east terrace close to Scott Avenue has been repaved in a pale brick herringbone bond, while the rest of the road surfaces remain asphalt.

Fig. 106: Brick setts used throughout the area

Around the core building, pedestrian pathways are typically formed with a sand-coloured bonded gravel, while loose gravel is used to the garden spaces at its south side.

Fig. 107: Bonded gravel surrounds the central historic buildings

Fig. 108: Loose gravel is utilised in the landscaped gardens

Street Furniture

Simple grey vertical lamp posts and grey illuminated bollards

Fig. 109: Contemporary bollards primarily located within the landscaped grounds

Part Three: Management Strategy

Summary

The Appraisal has assessed the quality and the condition of the Sutherland Grove Conservation Area. Site visits were undertaken between June and July 2022, when the area was observed and photographed.

This Appraisal has summarised the strengths and weaknesses of each character area and this management plan will set out a strategy to consolidate and enhance these strengths and prevent further erosion of the area’s special historic and architectural character.

The overall conclusion of the Appraisal is that, despite piecemeal erosion, all areas of the Sutherland Grove Conservation Area are worthy of inclusion. It is hoped that this clearer, more extensively illustrated Appraisal will assist the Development Management process in making more informed planning decisions in respect of the area’s character. It will also assist applicants to ensure their proposals contribute positively to the conservation or enhancement of the Conservation Area.

Furthermore, it is apparent that any further deterioration would endanger the character and appearance of the Conservation Area.

Under section 71 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 local planning authorities have a statutory duty to draw up and publish proposals for the preservation and enhancement of conservation areas in their area from time to time. Regularly reviewed appraisals, or shorter condition surveys, identifying threats and opportunities can be developed into a management plan that is specific to the area’s needs.

Design Guidance

Historic England recommends that the Appraisal is also a source of guidance for applicants seeking to make changes that require planning permission, helping to make successful applications.

The design guidance below encourages good quality design, which will help to both preserve and enhance the Conservation Area.

Dwellings within the Conservation Area, which are flats, do not benefit from Permitted Development Rights, and will always require planning permission to carry out alterations and extensions.

While the majority of development in the Whitelands character area is much later and modern in design, many of the principles below are still applicable, whereas like-for-like replacements are often the most appropriate and least intrudive options. Other works should consider the common material, scale, and harmony of appearance of the development, as well as the setting of the listed buildings surrounding.

Windows

Windows make a substantial contribution to the appearance of an individual building and can enhance or interrupt the unity of a terrace, so it is important that a single pattern of glazing bars should be retained within any uniform composition. Generally, windows follow standard patterns/styles. Later Victorian and Edwardian buildings often employed simple sash windows with simple glazing bar patterns, with the top and bottom sash either having one large pane, or a single central glazing bar.

The early 20th century saw a transition from sash to casement windows, and casement windows are the predominant window type within the Conservation Area. Generally, these are vertical windows with smaller fanlights, and were often square or diamond leaded windows, either to the entire window or limited to the fanlight. Occasionally, the fanlight would be more decorative stained glass. Few original examples of either style remain, though those which do are attractive features, which enhance the character of the area, and there are many good examples of modern replications.

Where timber windows survive these make an important contribution to the special character and appearance of the area; however, many have been lost and replacements are frequently of a different style and materiality which is unsympathetic to the historic appearance of the building and conservation area, disrupting the harmony and rhythm of the legible groups, and creating inconsistences within the otherwise congruous window typologies.

The quality of these replacements also varies, which dilutes the consistent appearance of the building groups, with some mimicking historic styles while others are inappropriate uPVC windows. Where timber windows have been replaced, these are often of poor quality, with thicker frames and higher reflectiveness, a variety of glazing bar formats, and there is a general lack of consistency to the approach to fenestration. Other inappropriate interventions include the introduction of new windows, which creates imbalance and visual disparity to the otherwise consistent scale and appearance.

It is encouraged that residents, in the first instance, retain and repair existing original timber windows. If replacement is required, all aspects of the window should be considered including opening type, glazing bar pattern, horns to sashes, and depth. Windows should be timber and are generally plain casement or with the appropriate square or diamond leaded window pattern. Sash windows should be single panes with no glazing bars or a simple two-over-two. Timber frames are not only the most appropriate option, but a natural material which helps reduce the use of plastics, often found in other windows. Timber windows also have the benefit of being more cost effective, being much more durable and repairable than alternatives, and there are options to maintain their appearance while introducing energy saving and noise reducing features.

Where original or historic windows survive, simple like-for-like replacements would likely cause the least harmful impact on the existing appearance of a building and therefore the character and appearance of the area. Like-for-like replacements also benefit from being able to be carried out without the need for planning permission. Existing windows can often be improved through secondary glazing, where an additional glass layer is installed behind an existing window. Secondary glazing is an unobtrusive option to increase efficiency, reduce noise, and avoid intervention to existing fabric, often performing as well, and lasting longer than double glazing. This approach also often benefits from not needing planning permission. Windows which have already been altered or replaced with modern materials should also follow a like-for-like replacement, whereas a replacement of traditional window details and materials is viewed as a heritage benefit.

Where appropriate and where there is justification for full replacement, slimline double and triple glazing with timber frames helps maintain a consistent appearance, while offering similar benefits to secondary glazing. Where double/triple glazing is accepted, black spacing bars and seals should be avoided – these should instead be white to blend with the frame. Trickle vents should be avoided or well concealed within the frame to maintain consistency with historic appearance.

More complex glazing patterns can often be housed within a double-glazed casing; however, this would have a much flatter appearance given the bars or other details would be entirely concealed within the glass panels and its suitability would be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Windows to contemporary development can vary in detail but it is still important to consider their design in relation to the character of the area.

Doors

Like windows, it is encouraged that residents, in the first instance, retain and repair any existing original timber doors. This is best for the environment, for the character and appearance of the area, and is often a more inexpensive solution to complete replacement. Simple modifications can often be carried out internally which improves the weatherproofing of the door without impacting its external appearance.

Existing styles of doors in the area generally manage to reflect the architectural style in which they are set, and original examples make a great contribution to the character of the area.

If a replacement is required, then it should match the original door for the property. Overly contemporary doors contrast with the traditional detailing of the host dwelling and are unsuitable.

Doors to Sutherland Grove are unique to the area - timber with a top window roundel divided into 6 panes, with three panels to the bottom and a central vertical mail slot.

Doors to the rest of the character are similar but with a more oval window without glazing bars, typically with a simple windowpane, though many have been replaced with a simple pattern or stained glass.

There is a notable absence of door furniture within the Conservation Area, and doors are often unembellished apart from letter flaps.

Roof Extensions

Roof extensions have become common in the Conservation Area, and given the significance of hipped roofs, are primarily found in the form of dormers inserted into the attic space. Hip to gable extensions are uncommon and not suitable, creating an imbalance between semi-detached pairs and infilling important gaps. While roof extensions can be a practical solution to utilising existing attic space and can successfully be implemented while maintaining the legibility of the roof form, many existing dormers are of an unsuitable scale and design, often conflicting with similar interventions within the same pair or typology, and their prevalence has eroded the roof scape substantially.

Dormer extensions are most suitable to the rear elevation where they are the least visible, and side dormers may be suitable dependent on the context of the host dwelling, with the spacing between houses and the setting of them in their respective gardens, meaning side elevations may be revealed, are key considerations. Where houses are closely spaced, inappropriately scaled side dormers can infill the gap between hipped roof forms and create a terracing effect similar to the conversion to a dormer.

Materials are key to incorporating new elements into existing buildings, and a sympathetic approach should be considered first. Appropriately sized dormers set within existing roof parameters are more suitably finished in a matching roof material, such as pantiles, to mitigate its appearance. Windows should be of a reasonable scale and match the host dwelling. Lead or zinc clad dormers have been introduced but these are often not suitable, contrasting sharply with the traditional domestic architecture and materials. Additional glazing to the dormer itself is not appropriate. Front dormers are also unsuitable.

Within the Gilbert Scott Character Area, buildings are intentionally designed to be identical, and are already to a greater scale than surrounding development, and so roof extensions are unlikely to be appropriate.

Other extensions

Houses in the Conservation Area were predominantly designed to have symmetrical or mirrored elevations, and the extension of the appearance of the front elevation, particularly within a pair, can cause a harmful imbalance and disrupt the wider streetscape. Detached dwellings are often too close together for a side extension to be practical and would contribute to an undesirable terracing effect. Given the irregular placement of dwellings in response to the curvature of the road, some locations may be well concealed, and extensions would be considered on a case-by-case basis. Where potentially suitable, it is typically preferred that extensions are finished in matching materials and are well set back from the principal façade to heighten a sense of subservience and minimise impact to the appearance of the elevation.

Garage Conversions

Garages add to the suburban character of the area and often form an important aspect of a front elevation, particularly when part of a balanced pair. There are some examples of successful infilling of garages, where the replacement infilling and window is sympathetic to the positioning and proportions of the garage itself. Extending forward or the creation of projecting bays is often inappropriate, introducing an uncharacteristic element to the host dwelling’s design and creating further imbalance within a pair.

Gardens

Gardens make a positive contribution and are a key characteristic of the homely domestic suburban character, from the which the significance of the area is derived. Planting can soften the appearance of the continuous frontage and heighten a suburban feel. A wealth of plant types can add variety in shape, height, colour, and seasonal coverage, which creates a consistent yet changing natural appearance.

Full hard landscaping creates uninviting frontages and should be avoided. Parking within gardens is similarly harmful to the character and appearance and will be resisted.

Boundaries

Boundary treatments vary throughout the area, often altered, or replaced, but there is consistency in material in scale. Timber would have originally been used, and the reinstatement of traditional timber boundaries and other timber elements would be a heritage benefit. Planting such as hedges are also increasingly common, and contribute to the suburban character, but should be of a variety that is suitable scaled to avoid concealing the garden from the public realm.

Boundaries are otherwise typically low brick walls which match the host dwelling. Metal is uncommon, as is render, and both should be avoided. Where boundaries are incapable of repair, new boundaries should be informed by the context of surviving historic examples to similar typologies as well as the context of adjacent boundaries, to reinstate a sense of cohesion to the streetscape.

The removal of part or all of a boundary wall is uncharacteristic and creates an overly urban appearance, in addition to an undesirable interruption to otherwise consistent boundary lines.

Lightwells

Lightwells can be discreetly inserted where garden space allows and should follow best practice outlined in the Housing SPD (2016) as well as policies in the Local Plan. Where lightwells are accepted, they should not be paired with full hard landscaping, but rather mitigated with soft landscaping elements, such as low maintenance shrubbery.

Painting and External Finishes

Painting is uncommon and should only occur if the existing location has already been painted, and an appropriate colour should be selected to maintain the overall neutral palette of the Conservation Area. Most often existing colours should be refreshed, or neighbouring houses can be referenced to create a harmonious appearance.

A variety of external finishes is a characteristic feature of the Conservation Area as a whole, and the approach to their treatment is similar to paint – where existing finishes can be repaired and restored, and new finishes not normally approved. Most often buildings would utilize contrasting materials, typically with the ground floor in another finish than the first floor, or with contrasting materials applied to architectural details, and this creates a visual richness to the area.

Frequently dwellings have been altered to apply a single finish to all elevations, most often white render, and this has eroded the character and appearance of the Conservation Area, creating a homogenized streetscape, and is not a suitable approach. The restoration of original finishes will be viewed as a heritage benefit.

Energy Efficiency

Introducing energy efficiency measures can be desirable to reduce carbon emissions, fuel bills, and improve comfort levels. It is important that the appropriate course taken should be informed by the context of the building being improved, with each building having different opportunities and restrictions. Not all solutions will be appropriate across the Conservation Area, and the ‘Whole Building Approach’ advocated by Historic England encourages a case-by-case approach, which fundamentally considers the context, construction, and condition of a building to determine which solutions would be the most suitable and effective. More detailed advice can be found within the Guidance Note Energy Efficiency and Historic Buildings: How to Improve Energy Efficiency 2018.

Solar Panels

Solar Panels and equivalent technology are most suitably placed on rear or side elevations where they are hidden from the public realm – principal elevations and roof slopes facing the public realm are less appropriate as they generally make the most substantial contribution to the character and appearance of the Conservation Area. New technologies, such as PV panels disguised as slates and sitting flush with roof materials, may be suitable in the appropriate context, and will be considered on a case-by-case basis.